Main Exhibit Page | Washington Bureau Chief | Mr. Reston Goes to China | Credits and Exhibit Sources

The New York Times’ Bay of Pigs

Found in RS 26/20/120, Box 3, Letters to the Executive Editor, 1968

Scotty undoubtedly left big shoes to fill at the Washington Bureau. Although his successor, Tom Wicker, was a talented columnist, the Bureau was no longer capturing front page headlines. It now looked as if their rival, the Washington Post, was poised to eclipse the New York Times. By late 1967, Turner Catledge, along with managing editors Abraham Rosenthal and Clifton Daniel, advised Punch Sulzberger to replace Wicker with Jimmy Greenfield, a former Time magazine correspondent. News of Greenfield’s ascension ignited a fierce power struggle between the Washington Bureau and the New York office, prompting Sulzberger to refer to the ensuing controversy as the ‘New York Times’ Bay of Pigs.[1]

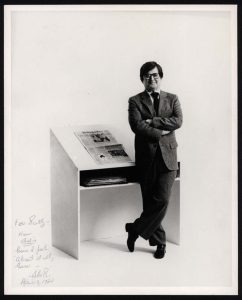

Found in RS 26/20/120, Unprocessed Awards, Artifacts, and Autographed Photos.

Scotty disapproved of the proposed appointment, fearing Greenfield’s lack of significant newspaper experience would alienate the talented reporters he had recruited during his tenure as Bureau Chief.[2] Indeed, most prestigious protégés, Anthony Lewis and Max Frankel felt insulted by the New York office; both men believed they were better suited to lead the Bureau.[3] On February 7, 1968, Scotty met with Punch in New York and warned him of the consequences of promoting Greenfield. Punch immediately rescinded his offer to Greenfield that same day to avoid further chaos[4]and blamed Turner Catledge for the calamity. At the urging of his mother, Iphiegene Sulzberger, Punch replaced Catledge with Scotty on May 2, 1968, to restore order to the Times. Although Scotty now possessed the power to remold the paper, he would soon encounter fierce opposition from his New York colleagues.[5]

Hostile Territory

When Scotty arrived in New York, he envisioned remodeling the Times in the mold of the Washington Bureau. He proposed establishing an elite group of correspondents from diverse subject specialties to cover the intellectual lifeblood of the world and transcend journalism’s penchant for covering war and politics.[6] Abraham Rosenthal, still bitter from the Greenfield debacle, lambasted the proposal, accusing Scotty of usurping his authority by attempting to create two classes of reporters: a chosen few serving under Reston while the rest reported to Rosenthal. Scotty withdrew the proposal, realizing the Times could not afford another public scandal.[7]

Scotty’s remaining tenure as Executive Editor was anti-climatic. Having little leeway to implement his reforms, he longed to return to Washington. Meanwhile, the mainstay of his column suffered because he was unable to maintain direct access to insiders, the necessary ingredient of any Washington column.[8] By August 9, 1969, Punch Sulzberger concluded the Times could not afford a part-time Executive editor, and replaced Reston with Abraham Rosenthal, further dissolving Scotty’s influence at the Times. ‘In short,’ he concluded, ‘I was not a successful executive editor.’[9] Despite this professional setback, Scotty would soon receive an unexpected invitation from China, enabling him to demonstrate again his enduring value to the New York Times.

Punch Sulzberger discusses why Scotty was not a successful Executive Editor, interviewed by John F. Stacks, Undated

Found in RS 26/20/157, Card File Box 2, Mooney, Dick and Punch Sulzberger

Continue to: Mr. Reston Goes to China

Footnotes

[1] Stacks, Scotty, 259-260; Tifft and Jones, 421-423; Memorandum for: Mr. A.O. Sulzberger from Turner Catledge, ca 1966, James B. Reston Papers, 1935-1995; Record Series 26/20/120, Box 32, Folder: Turner Catledge 1960, 1964, 1966, 1968, University of Illinois Archives.

[2] Frankel, The Times of My Life, 303; James Reston to Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Jr., January 14, 1968, Sulzberger, 1961-1996, James B. Reston Papers, 1935-1995; Record Series 26/20/120, Box 148, Folder: Sulzberger, Arthur Ochs Jr. (“Punch”), University of Illinois Archives; “Executive Editor,” 1989, James B. Reston Papers, 1935-1995; Record Series 26/20/120, Box 10, Folder: Executive Editor, 1989, University of Illinois Archives.

[3] Anthony Lewis to James Reston, January 8, 1968, James B. Reston Papers, 1935-1995; Record Series 26/20/120, Box 145, Folder: Lewis, Anthony, 1968-1995, University of Illinois Archives; Anthony Lewis to James Reston January 26, 1968, James B. Reston Papers, 1935-1995; Record Series 26/20/120, Box 145, Folder: Lewis, Anthony, 1968-1995, University of Illinois Archives; Max Frankel to James Reston, January 29, 1968, James B. Reston Papers, 1935-1995; Record Series 26/20/120, Box 33, Folder: Max Frankel IV 1960, 1964, 1968, 1973, University of Illinois Archives.

[4] Richard Harwood, “A New York Times Coup that was Almost Fit to Print,” The Washington Post, February 9, 1968, accessed March 3, 2016, ProQuest Historical Databases.

[5] Tift and Jones, The Trust, 423-426; Tape Recorded Interview with Dick Mooney,” Undated, John F. Stacks Papers, 1914-2003; Record Series 26/20/157, Card File Box 2, University of Illinois Archives.

[6] Stacks, Scotty, 266-267.

[7] Harrison E. Salisbury, Without Fear or Favor: The New York Times and Its Times (New York: Times Books, 1980), 411-413.

[8]Tape Recorded Interview with Dick Mooney,” Undated, John F. Stacks Papers, 1914-2003; Record Series 26/20/157, Card File Box 2, University of Illinois Archives.

[9] Reston, Deadline, 354.