“Minority groups in the United States, especially the non-white minorities, suffer crippling discrimination in jobs, housing, civil rights, and education. And they continue to face a school curriculum that, for them, is culturally impoverished. Ironically, it is also a curriculum which, in a different fashion, cripples white students and teachers by denying them the opportunity to learn about…other Americans who are non-whites.

From “Non-white minorities in English and Language Arts Materials,” by the NCTE Task Force on Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English

On the whole, NCTE has consistently been on the progressive side on issues of race. In his book, A Long Way Together: A Personal View of NCTE’s First Sixty-Seven Years, J.N. Hook explains the Council’s record:

“Throughout its life, [NCTE] had attempted to treat all groups — all students, all teachers, all its members — alike. It had, for instance, been one of the first professional organizations to insist that its conventions be housed only in places where there would be no racial discrimination. It had gone beyond that [in 1964 when] the Board of Directors…mandated that all associations affiliated with the Council be completely open with regard to race and ethnicity; within two years all affiliates — some in the face of considerable difficulty — had satisfied that requirement.” (1979, p. 232)

Until the 1940s, however, concerns regarding minority groups were largely non-existent in the Council’s official business. Hook describes that the Council’s Executive Committee minutes did not mention any minority issues, nor were any committees commissioned that specifically dealt with race. Awareness of race-related issues rose slightly during the early 40s with the publication of We Build Together: A Reader’s Guide to Negro Life and Literature, by Charlemae Rollins, in 1941. This book was the first NCTE publication to wholly focus on African American literature. Concerned that white students who did not receive any exposure to other races in their daily lives were more prone to racism, Rollins provided a list of books that counter the stereotypes being perpetuated at that time.

The 1960s mark when the NCTE took a much more active role in racial matters. As previously mentioned, in 1964, the Board of Directors mandated that the Council and its affiliates be open to all races and ethnicities (Hook, 1979, p. 232). In 1969, the NCTE formed the Task Force on Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English (p. 233). This Task Force primarily focused on encouraging teachers to use more works authored by minorities, as well as to discourage discrimination in textbooks. The Task Force would prove successful, releasing several publications and garnering media attention.

As the decades passed, NCTE still maintained its interest in minority affairs, advocating for fair representation and diversity. To learn more about how NCTE became an advocate for minority groups, take a look at the featured topics below:

- We Build Together: A Reader’s Guide to Negro Life and Literature

- Board of Directors Meeting Minutes, 1945

- Formation of the Task Force on Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English

- Criteria for Teaching Materials in Reading and Literature

- Publicity: “Native Myths, Tales Open ‘Storehouse'” and “NCTE Task Force to Combat Racism and Bias in Textbooks”

- Searching for America

- Non-White Minorities in English and Language Arts Materials

We Build Together: A Reader’s Guide to Negro Life and Literature

The first NCTE publication to focus on race, We Build Together: A Reader’s Guide to Negro Life and Literature by Charlemae Rollins, listed books by and about African Americans and their lives. Troubled by the racism in schools, the author theorized that stereotypes, combined with the lack of personal ties to any African Americans, were fueling the students’ harmful attitudes. Rollins wrote: “Some white youth will never have the opportunity to know intimately Negroes who live as they do…If such young people are introduced to a few books which portray Negro life not only as it is lived by Richard Wright’s Bigger Thomas…but as it is lived by Florence Means’s Harriet in Shuttered Windows…they will lose some of their feelings of condescension and they will gain in understanding” (p. 3). Rollins then provided a bibliography she thought gave a realistic, accurate portrait of African American life. Learn more: 15/71/809

Item: First edition of We Build Together: A Reader’s Guide to Negro Life and Literature (1941)

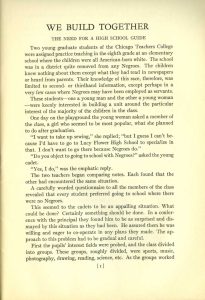

1945 Board of Directors Meeting

In 1945, the NCTE Board of Directors took direct action against racism. During the Board’s annual meeting, the Committee on Intercultural Relations presented a resolution proposing that NCTE “hold annual meetings of the Council only in those cities in which hotels, particularly the headquarters hotel, accord members of the Council rooms and dining room service regardless of race or religion.” The Board of Directors passed and adopted this resolution. Learn more: 15/70/001

Item: Board of Directors Meeting Minutes (1945)

A New Task Force

One of the most significant actions the Council took regarding race-related matters was the establishment of the Task Force on Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English in 1969. This task force helped to continually bring attention to issues concerning minorities and their representation. Ernece B. Kelly was the first chair of this committee. Her first responsibility was to recruit members. In her invitations to potential members, she described the goals of the task force. The first objective of the three she listed read: “The task force will assess the nature and breadth of the phenomenon of the continuing development of texts and tests which discriminate against cultural and racial groups.” Learn more: 15/73/008

Item: Correspondence inviting potential members (1970)

Criteria for Teaching Materials in Reading and Literature

One of the first major achievements of the task force was its publication of Criteria for Teaching Materials in Reading and Literature in 1970. This document defined the problems with current teaching materials and offered a list of criteria to select appropriate classroom texts. Its rationale read in part: “The school experience is not the sole force that shapes self-images and attitudes toward other persons, races, and cultures. But in the measure that school does exert this influence, it is essential that the materials it provides foster in the student not only a self-image deeply rooted in a sense of personal dignity, but also the development of attitudes grounded in respect for and understanding the diversity of American society.” NCTE’s Board of Directors officially adopted this statement of criteria. Learn more: 15/73/803

Item: Copy of Criteria for Teaching Materials in Reading and Literature (1970)

Gaining Publicity

The Task Force was able to attract press attention soon after its inception. On December 12, 1970, the Capital-Journal in Salem, OR., featured a story on Native American literature and the decision of a group of Native American scholars to more openly share their literary traditions. Task force member, Montana Rickards commented on the importance of this event: “Now at last a group of Native Indian scholars is emerging which, with the trust of their people, may unlock at last this long-neglected element of American culture.” The promotion of Native American literature was an important cause of the task force. The Chicago South Suburban News ran a story on the task force itself a couple of weeks later on December 26, 1970. It highlighted the task force’s recent publication of Criteria for Teaching Materials in Reading and Literature. The article began: “A nationwide effort to notify school textbook publishers and educators of new criteria for purging the materials they publish and the lessons they teach of possible racism and bias is the major project of a special task force of the National Council of Teachers of English.” Ernece Kelly was quoted throughout the article, explaining the new criteria her task force developed. Learn more: 15/73/008

Item: Newspaper clippings about the Task Force (1970)

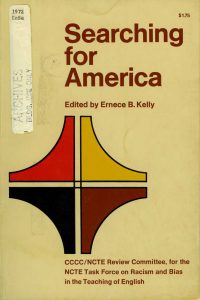

Searching for America

In 1972, NCTE published the anthology, Searching for America, edited by Ernece B. Kelly. The book, written together by fellow members of the task force, provided evaluations and essays on American literature taught in college and whether they fit the criteria put forth by the task force. In the introduction, Kelly wrote, “It is our hope that in the hands of teachers and administrators this publication will be a catalyst for change, both in individuals and in groups, as they go about the business of selecting and criticizing literary texts.” Learn more: 15/73/803

Item: Copy of Searching for America (1972)

Non-white Minorities in English and Language Arts Materials

In 1978, the task force revised its Criteria for Teaching Materials in Reading and Literature and renamed its statement, Non-White Minorities in English and Language Arts Materials. The task force acknowledged that many publishers moved in a positive direction and have included more “multi-ethnic materials in their products” since 1970. However, the task force believed there were still problems with the representation of non-white minorities. The statement in this brochure sought to identify and provide a remedy to those issues. Learn more: 15/73/803

Item: Copy of Non-White Minorities in English and Language Arts Materials (1978)