“The reasons for [the] great American success story of [Reader’s Digest] are many…. Add to this the rapid-transit mentality of the American public which demands its reading in tabloid form or in ‘twenty words — no more, no less.’ Consider further the fact that America is the greatest pill-taking nation in the world; hence its acceptance, Reader’s Digest style, of all thought and opinion in capsule form.”

Samuel Beckoff, “The Rainbow,” The English Journal (1943)

As a national organization with over 54,000 members, the National Council of Teachers of English has the clout to be heard across the country. The Council’s platform gives English teachers the ability to broadcast their concerns on contentious issues to a national audience. As already illustrated in previous exhibits, such as the NCTE’s advocacy for minority groups and its rallying against doublespeak and censorship, the Council does not shy away from controversy.

However, even when the Council is not necessarily looking for national attention, that does not stop it from being drawn into controversy. Language can provoke heated debate and naturally drag English teachers in as experts. In Women and Language in Transition, Allen Pace Nilsen, a member of the NCTE Committee on the Role and Image of Women in the Profession, provided this anecdote:

“In a startling change from the days when the confession of being an English teacher served as a STOP sign to light social conversation, English teachers began to be sought out at cocktail parties to either settle disputes or add fuel to the fire as people argued about the feminist movement and its relation to language” (1987, p. 38)

Nilsen was referring to the 1970s and the debate over sexist language. When the NCTE produced Guidelines for Nonsexist Use of Language in NCTE Publications, following what many other publishers were doing at the time, the pamphlet received national attention. Conservative columnist, William F. Buckley Jr., blasted NCTE’s guidelines, his criticism appearing in newspapers across the nation.

Other issues that propelled NCTE into partisan politics included a conflict with Reader’s Digest during World War II and the relatively recent attempt at establishing national standards in English teaching in 1996. To learn more about these controversies, take a look at the featured topics below:

- NCTE and Reader’s Digest

- “Summary and Report,” The English Journal, 1943

- “The Rainbow,” The English Journal, 1943

- Board of Directors Meeting Minutes, 1944

- Newspaper Clipping: “Propaganda Study Scares ‘Digest’ Staff,” September 1944

- Board of Directors Meeting Minutes, 1945

- NCTE and Eliminating Sexist Language

- Guidelines for Nonsexist Use of Language in NCTE Publications

- Sexism and Language

- NCTE and Standards

- NCTE/IRA Standards for the English Language Arts

- The Controversy of the NCTE/IRA Standards

NCTE and Reader’s Digest

“Summary and Report,” The English Journal

In what J.N. Hook refers to as “The Reader’s Digest Fiasco,” a conflict between the news magazine and NCTE began with a brief article in the “Summary and Report” section of the English Journal. The column summarized charges leveled at Reader’s Digest by the left-wing newspaper, In Fact, namely accusing the magazine of being antidemocratic, antilabor, and anti-Semitic. In A Long Way Together: A Personal View of NCTE’s First Sixty-Seven Years, Hook describes that “a month later the English Journal reported that Reader’s Digest representatives had called the In Fact claims ‘baseless falsehoods'” (1979, p. 139). As a result, NCTE President John DeBoer asked the Committee on Newspapers and Magazines to “investigate the usefulness and soundness of the Reader’s Digest as a teaching aid in the war situation” (p. 139). Learn more: 15/71/801

Item: Copy of the English Journal (Feb. 1943)

“The Rainbow,” The English Journal

Before the report was released, two more articles on Reader’s Digest were published in the June 1943 edition of the English Journal. One article praised the magazine for its usefulness as a reading tool, while the other lambasted it. The critical article, “The Rainbow,” written by Samuel Beckoff, repeated many of the accusations made by In Fact. Beckoff believed that many of the authors who write for the magazine hampered the war effort. The positive article, “Reading for Pleasure and Profit,” written by Herbert A. Landry, cited statistics showing that Reader’s Digest improved students reading skills at double the normal rate. Hook reveals, however, that the author was “perhaps then and apparently a year later an employee of Reader’s Digest” (p. 139). Learn more: 15/71/801

Item: Copy of the English Journal (June 1943)

1944 Board of Directors Meeting

The report on Reader’s Digest that DeBoer had asked the Committee on Newspapers and Magazines to conduct was completed in 1944. The Executive Committee, however, refused to publish the report, which made many of the same criticisms as Beckoff’s article. The NCTE president at that time, Angela Broening, led the opponents of the report. The resolution, which passed five to two, stated: “We have found the report to be insufficiently documented and we do not feel that it is free from bias and prejudice.” It further explained that Reader’s Digest had recently followed through on suggestions made by NCTE, including presenting both sides on controversial issues. When the Board of Directors convened in November 1944, they discussed the Executive Committee’s decision. The Board decided to ask the Executive Committee to appoint a new committee on Magazine Study to publish a report on Reader’s Digest. Learn more: 15/70/001

Item: Board of Directors Meeting Minutes (1944)

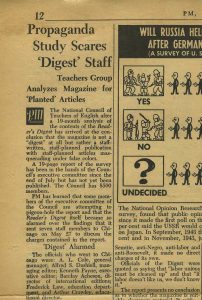

“Propaganda Study Scares ‘Digest’ Staff”, 1944

The conflict between NCTE and Reader’s Digest attracted the attention of the leftist newspaper, PM, which published an exclusive article leading up to the events at the 1944 Executive Board meeting and the Reader’s Digest report. “PM has learned that some members of the executive committee of the Council are attempting to pigeon-hole the report and that the Reader’s Digest itself became so alarmed over the findings that it sent seven staff members to Chicago on May 27 to discuss the charges contained in the report.” The article went on to share some of the findings from the report of the Committee on Newspapers and Magazines, which was never officially published. Learn more: 15/71/810

Item: PM Sunday newspaper clipping (September 10, 1944)

1945 Board of Directors Meeting

Finally, at the 1945 Board of Directors meeting, the Reader’s Digest controversy came to a close. The new committee determined that 1) the investigation of only one magazine is inappropriate, 2) the Executive Committee was correct for not publishing the report but rebuked Broening for lacking “complete objectivity,” and 3)the Council should study and publish a pamphlet on the use of periodicals in the classroom. In 1950, the Council published Using Periodicals, which “mentioned Reader’s Digest only in connection with other publications” (Hook, 1979, p. 143). Learn more: 15/70/001

Item: Board of Directors Meeting Minutes (1945)

NCTE and Eliminating Sexist Language

Guidelines for Nonsexist Use of Language in NCTE Publications

“The man who cannot cry and the woman who cannot command are equally victims of their socialization.” In 1976, the Council published Guidelines for Nonsexist Use of Language in NCTE Publications, which decried gender roles and advocated a more gender-neutral language. The NCTE argued that language has a powerful influence in reinforcing these roles. “Thought and action are reflected in words, and words in turn condition how a person thinks and acts. Eliminating sexist language will not eliminate sexist conduct, but as the language is liberated from sexist usages and assumptions, women and men will begin to share more equal, active, caring roles.” This pamphlet stirred up controversy on the national level. In particular, William F. Buckley Jr. blasted NCTE for its recommendations, accusing the organization as being more concerned for “fashionable sociological skirmishes” than good prose. Learn more: 15/71/824

Item: Guidelines for Nonsexist Use of Language in NCTE Publications (1977)

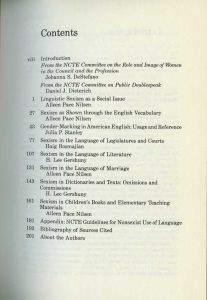

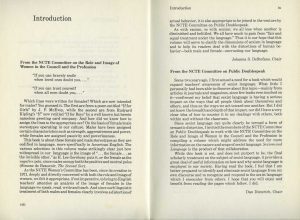

Sexism and Language

Closely following the pamphlet, Sexism and Language was published a year later in 1977. The book was the result of the combined efforts of the NCTE Committee on Public Doublespeak and the NCTE Committee on the Role and Image of Women in the Profession. Similar to the pamphlet, the book stressed that sexist language reinforced gender stereotypes. Chair of the Women’s Committee, Johanna S. DeStefano wrote: “It is our hope that this volume will serve to clarify the dimensions of sexism in language and to help its readers deal with the distortions of human behavior — both male and female — encrusting our language.” Each of the eight chapters explored a different facet of sexism in language, including in dictionaries, children’s books, and literature. Learn more: 15/73/803

Item: Sexism and Language (1977)

NCTE Standards in English

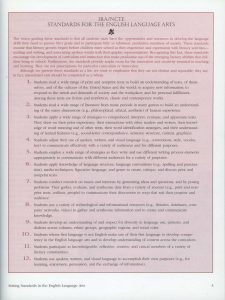

Standards for the English Language Arts

In 1992, the U.S. Department of Education issued a grant to the NCTE and the International Reading Association (IRA) to establish national standards for English education. After the first two years, the government stopped funding for the project, claiming there was insufficient progress. Nevertheless, the NCTE and IRA continued to work on formulating these standards, and in 1996, they published Standards for the English Language Arts, the culmination of four years of work “involving thousands of educators, researchers, parents, policymakers, and others across the country.” The reaction of both the public and the profession, however, were mixed. In “The Little Standards that Couldn’t,” author Henry B. Maloney outlined the many critiques made against the document, the most prominent being that the standards were more like philosophical guidelines than achievable goals. However, those in favor of the standards preferred this more conceptual approach. “It is designed to be discussed, not merely followed,” Mark A. Faust and Ronald D. Kieffer stated in their article, “Why We Ought to Stand by the IRA/NCTE Standards for the English Language Arts” (1998, p. 542). While the Standards did not achieve the national implementation that was originally hoped for, it did provoke serious discussion about English educational standards on the national level. Learn more: 15/71/826

Item: Standards for the English Language Arts (1996)

Controversy over NCTE/IRA Standards

In Reading the Past, Writing the Future: A Century of American Literacy Education and the National Council of Teachers of English, Donna E. Alvermann interviewed by e-mail three individuals who participated in crafting the 1996 Standards. She weaved their responses into one cohesive narrative that identified many of the conflicts involved in the project. The tension between developing specific standards or broad guidelines was present early on in the work. Wary that the government would turn specific standards into mandates, the NCTE and IRA favored the more conceptual approach. The interviewees speculated that this approach was the major breaking point that led the Department of Education to end its funding for the project. The NCTE and IRA stepped in to fund the project fully, bringing it to fruition. Read more: 15/71/824

Item: Reading the Past, Writing the Future: A Century of American Literacy Education and the National Council of Teachers of English (2010)