Exhibit Main Page | Part I: Overcoming Barriers | Part II: Securing Rights | Part III: Empowering Individuals | Part IV: Celebrating Achievements | Guide to Disability Research Resources

To accommodate the new students, the University authorized ramps to make six classroom buildings accessible. The buildings included Lincoln Hall, Gregory Hall, Noyes Laboratory, the Natural History Building, the Library, and the Illini Union. In 1955, University architects agreed that all future U of I buildings would be designed to accommodate students with disabilities. That same year the Rehabilitation-Education Program was added (in part) to the University budget. The Rehabilitation Program was gaining momentum and public attention. By the spring of 1954, over 90 students were enrolled in the program and 170 more had applied for the fall semester.

Many legislative actions concerning employment, housing, and public building access and equal rights for people with disabilities grew from activities launched at the U of I. The Rehabilitation-Education Center engaged in research programs designed to make the world more accessible to people with disabilities. In fact, results of research on wheelchair accessibility in home design still inform current standards. Key questions that research considered: How steep should ramps be for access by persons with disabilities, with varying degrees of disabilities? What materials provide the best traction and durability?

Standards were set through research conducted on the “ramp that led to nowhere.” This ramp was built just outside the Rehab Center and was adjustable to heights up to one story. Researchers changed its slope and length by raising or lowering the ramp and pounding pegs in the predrilled holes in the vertical posts.

Approximately seventy-five students in wheelchairs with various degrees of disability were tested using this ramp. Students were timed ascending and descending the ramp and asked to evaluate their degree of difficulty on each combination of pitch and length. The examiner also evaluated the degree of difficulty he observed in the individual’s negotiation of the ramp, and the effect that wheeling seemed to have on the participant.

Developed at the U of I in 1961, the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) Standards A117-A contain specifications for making buildings and facilities accessible to people with disabilities. Topics considered include appropriate grades for ramps and turning radii. These standards are reviewed every five years and are upgraded when technological or other changes warrant. When ANSI A117-A (1961) was reviewed by architects, engineers, and people with disabilities for the Americans with Disabilities Act Architectural Guidelines (ADAAG), no improvements were suggested. Equally impressive is the speed with which these standards emerged: while the average time to develop ANSI Standards is 5-7 years, the University of Illinois completed A117.1-A in a little over a year because of previous research and experience. These standards help show that public places of entertainment can accommodate people using wheelchairs as participants and spectators.

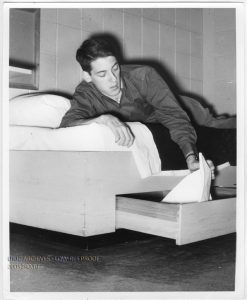

The proper design of furniture in a college residence is essential. This picture shows a conventional bed with drawers built into the base of the bed. A student with quadriplegia illustrates his independence in self-care.

Testing turn-around space using one fixed wall and three movable wall panels. Research indicates that in most instances a smaller person in a wheelchair requires as much or more space than a larger person in a standard wheelchair.

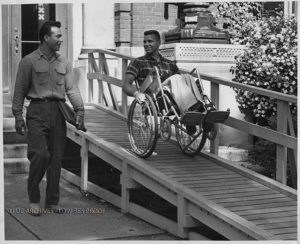

Dean Nosker demonstrates a rear wheel balance technique for negotiating inclined surfaces and ramps. The ramp he is using is just one solution to make an inaccessible building usable to people with disabilities. Studies suggest that ramps accommodate as much as 85 percent of the traffic entering or leaving a building.

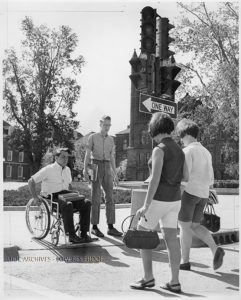

Curb cuts on campus promote accessibility for people in wheelchairs and can also serve as a directional guide for the blind.

When students first came to the Champaign-Urbana campus, there were two transportation options available: push to class or schedule a ride with someone who had a car. In 1952, that changed when the “Blue Bulls,” two buses with hydraulic lifts, made their debut. Seats on one side were removed to allow wheelchair access to the remaining row of seats and to accommodate storage. These buses laid the groundwork for accessible metropolitan transportation systems now available nationwide.

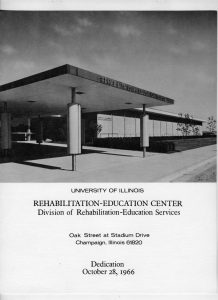

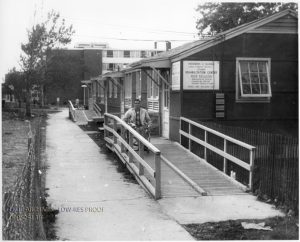

Authorized by the Board of Trustees on May 17, 1961, the new facility would replace the two parade ground unit barracks which housed 37 full- and part-time staff members. In the fall of 1965, the Division of Rehabilitation-Education Services moved into its new home on the western edge of campus. By June 1966, the program could boast of 381 graduates-many with advanced degrees. The new Rehabilitation Center was officially dedicated on October 28, 1966.

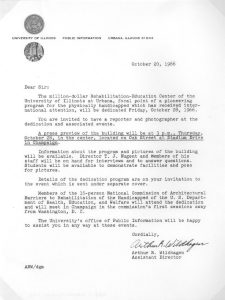

Promotional Materials, Opening of the New Rehabilitation Center October 1966

Neurological and muscular examinations and evaluations, functional training, training in special skills, and various exercise and therapy routines were all part of the services of the Rehabilitation-Education Center. The program’s many innovations and successes helped it maintain a high profile that attracted the attention of the media and many politicians as well.