Main Exhibit Page | Washington Bureau Chief | A Stormy Tenure as Executive Editor | Credits and Exhibit Sources

An Unexpected Invitation

Found in RS 26/20/121, Box Unprocessed Photographs + Overszie China + Russia Trip

Scotty’s trip to China occurred amidst the early steps towards reopening diplomatic relations between the United States and China after two decades of dissociation. Chinese officials granted Scotty and Sally visas to visit the country in May 1971, believing the renowned journalist would help reintroduce China to the Western world before President Nixon’s historic trip to the country in February of 1972.[1] Indeed, Scotty was impressed by what he witnessed upon reaching mainland China on July 8, 1971, noting that the Chinese people represented the enduring spirit of humanity. ‘They have been…plundered and dismembered for centuries by scoundrels, foreign and domestic,’ Scotty observed, ‘yet they have not only survived but managed somehow to shinny up near the top of the greasy pole.’[2]

Found in RS 26/20/120, Box 123, Working Files 1974-75, Acupuncture

The most memorable part of the trip, however, occurred when Scotty sought treatment at the Anti-Imperialist Hospital in Beijing on July 17, 1971, for appendicitis. Although the doctors successfully removed Scotty’s appendix, he experienced lingering pain in his stomach. Dr. Li Chang Yuan, the hospital’s acupuncturist, alleviated Scotty’s discomfort by inserting three needles below Scotty’s right elbow and kneecaps. The procedure was a success, leading Scotty to write a column introducing American readers to acupuncture. Over the next several years, Scotty received a deluge of letters from desperate readers inquiring if acupuncture could cure them of their ailments.[3] As he convalesced at the hospital, Scotty received a visit from Chinese Premier Chou En-Lai. The Premier, fearing the prominent American journalist would die in China, agreed to an interview with Scotty to spur his recovery.[4] Scotty would once again have a front-page story in the New York Times.

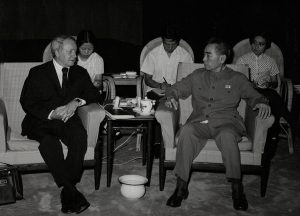

Scotty Interviews Chou En-Lai

On August 9, 1971, Scotty met with Premier Chou En-Lai in the Great Hall of the People for a five-hour interview. The two discussed a range of topics, including the Vietnam conflict.[5] The most controversial moment occurred when Scotty suggested that President Nixon was reopening diplomatic relations with China to atone for his past red-baiting of adversaries who sought détente with China.[6] Scotty’s comments incensed Nixon, who believed Reston was attempting to sabotage his upcoming trip to China. Max Frankel, a Reston protégé and the Times’ Washington Bureau Chief, bore the brunt of Nixon’s paranoia and fury: the president banned Times’ reporters from accompanying him on his February 21, 1972, trip to China.Frankel barely managed to win a concession from Nixon’s staff to join the president’s entourage on the journey.[7]

Scotty’s interview with Chou En-Laid represented one of the crowning highlights of his fifty-year career at the New York Times. He would spend his remaining decades navigating the jarring sociopolitical tectonic shifts in American society, discovering that his moderate views and close relationships with powerful figures reduced his credibility among a new generation of Americans who distrusted their leaders after Vietnam and Watergate. As he aged, Scotty sought refuge in his ownership of his small weekly newspaper, the Vineyard Gazette, and writing his memoirs, reminiscing over his enduring legacy.[8]

Found in RS 26/20/121, Box Unprocessed Photographs + oversize China and Russia Trip, China–Peking and Area Photographs

Continue to: Credits and Exhibit Sources

Footnotes

[1] Stacks, Scotty, 308; Reston, Deadline, 381; “Reston 3d Times Writer Given a Visa by Peking,” The New York Times, May 22, 1971, accessed March 14, 2016, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[2] James Reston, “Letters from China: V,” The New York Times, August 18, 1971, accessed February 22, 2016, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[3] Reston, Deadline, 383; James Reston, “Now, About My Operation in Peking; Now Let Me Tell You About My Appendectomy in Peking…” The New York Times, July 26, 1971, accessed February 22, 2016, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[4] Stacks, Scotty, 309.

[5] Reston, Deadline, 384-386; James Reston, “Chou Looks to Broad Talks with Nixon,” The New York Times, August 10, 1971, accessed February 22, 2016, ProQuest Historical Databases; James Reston, “An Evening with the Premier of China,” The New York Times, August 10, 1971, accessed February 22, 2016, ProQuest Historical Databases.

[6] “Official Transcript of the Wide-Ranging Interview with Premier Chou in Peking: Effort by the Two Sides in Korea to Achieve Reunification is Proposed by Chou,” The New York Times, August 10, 1971, accessed February 22, 2016, ProQuest Historical Databases.

[7] Stacks, Scotty, 312-313; Frankel, The Times of My Life, 348-349; Tape Recorded Interview with Max Frankel,” Undated, John F. Stacks Papers, 1914-2003; Record Series 26/20/157, Card File Box 1, University of Illinois Archives.

[8] “Tape Recorded Interview with David Halberstam,” Undated, John F. Stacks Papers, 1914-2003, Record Series 26/20/157, Card File Box 1, University of Illinois Archives; Stacks, Scotty, 327-331, 335-336.