Main Exhibit Page | Humble Beginnings | The University of Illinois | The Adopted Sulzberger | The Dumbarton Oaks Conference and Senator Vandenberg | Credits and Exhibit Sources

Found in RS 13/1/21 Box 1, Reston, James B. 1934-1944

Cub Reporter

While most young men in the 1930s would be thankful to have a job, Scotty was not content with The Daily News, determined as he was to make a name for himself in prestigious newspapers like The New York Times. By 1934, his ambition led him to a position as the traveling press secretary for the Cincinnati Reds and enabled him to contact newspapers in neighboring cities. On one such trip he met Milton Caniff, a friend who penned the Dickie Dare comic strip for the Associated Press. Caniff introduced Scotty to his editor, who hired Scotty to work on the sports feature page. Scotty had finally broken into the big leagues.[1]

Scotty occupied a variety of positions while at the AP. At one point, he was a columnist for A New Yorker at Large, chronicling New York’s elite society.[2] During this period, Sally and Scotty reunited in New York on November 1934, the first time in two years. The reunion strengthened their commitment to one another and they married soon thereafter on December 24, 1935. She gave birth to their eldest son, Richard Reston, two years later in June of 1937.[3] The couple would have two other sons, James Barrett Reston Jr. (1941) and Thomas Reston (1946).

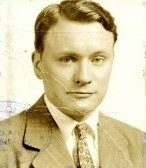

Found in RS 26/20/120, Box 4, Passports 1934-1986

Conflict in Europe

The couple’s bustling life in New York would not be for long. The AP transferred Scotty to its London bureau in May 1937 to cover sporting events, although Scotty was no longer content with sports amidst the ascent of fascism in Europe.[4] Reston reflected that ‘international politics, for sheer impertinence, trickery and graft, is the only thing in my experience to surpass sports. The only difference actually is that…sports principals are made to account in action for their claims and promises. In politics, this is not true.’[5]

Scotty entered this fascinating arena when the New York Times hired him on September 1, 1939, as a correspondent for the paper’s London bureau. Despite witnessing firsthand the British people’s valiant efforts to withstand the Nazi menace, Scotty was dissatisfied with his work. He believed the British government’s zealous censorship policies compromised his integrity. The Ministry of Information, for example, would only allow reporters to document Germany’s brutality and forbade any mention of Allie atrocities.[6]

Dinner with the Sulzbergers

When an illness briefly incapacitated Scotty, the London Bureau gave him a reprieve from these ethical dilemmas and transferred him to the United States to recover. Scotty’s return garnered the notice the Times’ publishers, Arthur and Iphigene Sulzberger. The fact that he was an eyewitness to the burgeoning war in Europe intrigued the couple, who desired to know more about the conflict. The Sulzberger’s would become ardent supporters of Scotty over the next several decades, spurring jealous colleagues to give Scotty a new nickname:‘the adopted Sulzberger.’[7]

Scotty discusses his evolution from sports reporting to foreign affairs at the Associated Press, interviewed by James Reston Jr., May 7, 1978

Complete interview found in RS 26/20/120, JBR Jr. Interviews JBR and SFR

Continue to The Adopted Sulzberger, 1940-1943

[1]Stacks, Scotty, 40-41, Reston, Deadline, 40-42; “Tape Recorded Interview with James B. Reston,” December 25, 1977, James B. Reston Papers, 1935-1995, Record Series 26/20/120, University of Illinois Archives.

[2] “Tape Recorded Interview with James Reston,” May 7, 1978, James B. Reston Papers, 1935-1995; Record Series 26/20/120, University of Illinois Archives.

[3] Reston, Deadline, 50-51; Stacks, Scotty, 46-47, 49.

[4] “Tape Recorded Interview with James Reston,” December 25, 1977, James B. Reston Papers, 1935-1995.

[5] Stacks, Scotty, 52.

[6] Ibid, 54-55, 57, 59-60, 61-62.

[7] Ibid, 65-66, 67.