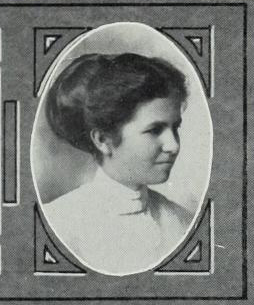

By all accounts, Alida Cynthia Bowler, psychology graduate of the University of Illinois in 1910 and 1911, was an extraordinary woman.

Alida Bowler entered the University in 1908 and in doing so became part of a Progressive Era in education that extended from the 1890s-1930s. To Progressive Era proponents, the purpose of education was not just the acquisition of skills, but the realization of students’ potential and the ability to use those skills for the greater good. According to education reformer John Dewey, “Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself.”

Bowler was an active participant in student life, including Kappa Alpha Theta, Classical Club, Phi Delta Psi, Phi Beta Kappa, and a recurrent May Day Folk Dancer. In the early 1900s, dances and concerts were primary social activities for sorority girls outside of coursework and studies. As a Kappa Alpha Theta, Bowler participated in another popular pastime–“dress up” parties. These impromptu occasions centered around recreating real life events, such as weddings, using costumes to capture the chosen theme.[1] After graduating with her Masters in 1911, she taught English at her home high School in Alton, IL until 1915.

Record Series 39/2/24

Over the next several decades, Alida Bowler’s life confirmed the Progressive belief that education improved citizenship and produced the leaders needed for economic modernization. At the end of the nineteenth century, women were the moral guardians and protectors of the home. During the Progressive Era, female reformers argued that women should exert their moral authority over public issues such as public sanitation and education, which ultimately affected the home. Women’s organizations worked for reform, conducted research, implemented programs, and lobbied for legislative issues dealing with education, healthcare, and political corruption.

The Great War significantly changed the trajectory of the country and the role of women outside the home. During the War, Alida Bowler served in France and Romania with the Red Cross, and continued working in Romania until 1920 with the American Relief Committee. Russian refugees fled Odessa when the city fell to the Bolshevik army and were fed, clothed, and received medical attention for typhus; “Nonetheless the Russian Volunteer Army loved us none the more though they continued to eat our corned beef and wear our pajamas,” observed Bowler.[2]

October 6, 1964

Record Series 41/72/27

Upon her return to the United States, Bowler continued to push socially-proscribed gender boundaries. During her career she was Senior Economic Analyst and general consultant on juvenile delinquency for the Children’s’ Bureau (U.S. Dept. of Labor), Secretary for the American Indian Defense Association, and Director of Public Relations for the Chief of Police in Los Angeles, California. Most notably, she was the first woman to hold the post of Director of Carson Indian School & Reservation in 1934.[3] The Bureau of Indian Affairs established this boarding school near Carson City, Nevada in 1890 to train and educate Native American children with an original goal of assimilation. After several years overseeing the school, Bowler noted that “The Indian in Nevada…is still discriminated against socially and exploited economically. He is primarily the under-paid agricultural season laborer upon whom the big cattle and sheep interests depend for cheap labor at certain seasons…He lives on a substandard level, and his smug white employer asserts that the Indian is perfectly content at the level and neither desires nor deserves a hand up.”[4]

Alida Cynthia Bowler devoted her life to helping others in need, including victims of war, troubled children, and the racially downtrodden. The daughter of a farmer from Alton, IL, she exemplified the Progressive vision shared with the likes of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Susan B. Anthony, Emma Goldman, and Jane Addams.

[1] Kappa Alpha Theta Delta Chapter, 1895-1925, Kappa Alpha Theta History, Record Series 41/72/27, University of Illinois Archives.

[2] “Alida C. Bowler ’08 Tells of Rumanian Relief Work,” Daily Illini, January 8, 1920, p.8.

[3] The Semi-Centennial Alumni Record of the University of Illinois, 1918.

[4] Rusco, Elmer R., “The Indian Reorganization Act in Nevada: Creation of the Yomba Reservation,” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, vol. 13 no. 1 (1991), p. 81.