John Philip Sousa’s Newly Uncovered Letters

By Scott Schwartz

Recently the Sousa Archives acquired the Frances Carter and Marjorie Moore Sousa Research Files documenting John Philip Sousa’s relationship with his family while America’s March King. The collection includes Sousa’s letters to his wife; early photographs of Sousa’s bands; original scripts and schedules for 20th Century Fox’s 1952 movie, Stars and Stripes Forever; memorabilia; and magazine articles.

The documents were compiled by Sousa’s daughters, Helen and Jane Priscilla, and Marjorie Moore, the Marine Band’s first historiographer, to fact-check the script for Fox’s biographical movie about Sousa’s life and music.

Sousa’s influence on late 19th– and early 20th-century music is well known, but very little is known about his relationship with his family. As a traveling bandleader Sousa gave thousands of concerts between 1892 and 1932 and spent months away from his family.

Sousa’s wife Jane and children accompanied him for some portions of tours, but he usually travelled without them. These absences occasionally created tensions with his family, and his letters home document their very private lives.

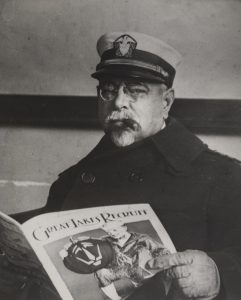

In WWI in 1917 Sousa offered his services to the U.S. Marines and then the U.S. Army, but he was turned down because of his age and became frustrated by their responses. However, the commandant of the Great Lakes Naval Center offered Sousa a commission as a lieutenant in the United States Naval Reserve to organize and train Navy bands for the war.

Sousa’s short letter to Jane on September 21, 1917, announcing his Navy commissioning probably caught her by surprise because he had temporarily disbanded his civil band. He wrote, “Dearest Jane…No dear, I am not in the Navy as a regular but as a Reserve Officer ordered to active duty which gives me as long as I am under orders as an active Lieutenant with the pay and allowance of a Lieutenant (Senior Grade) of the Navy.”

While on tour with the Great Lakes Naval Battalion band on May 17, 1918, Sousa wrote, “Dearest Jane, I am here with the band until Tuesday night, then to Cleveland [and] N.Y. for the war bond concert and some work in connection with the Atlantic Fleet…Hope to see you on the 28th. With much love and kisses, devotedly, Philip.” However, by early September Sousa’s civilian band was reconstituted to complete their Willow Grove Park performances and he left for Chicago rather than returning home. This annoyed Mrs. Sousa. He wrote on September 13, “Dear Jane, I am enclosing your allowance for September. It must be a delicious and satisfying feeling to receive an allowance of $1,000 per month, and also possess the right to give your husband hell when it so moves you…Am tired. Affectionately, Philip.”

Sousa’s tenure with the Naval Battalion Band ended in 1920, but his commission with the Navy for a dollar a year allowed him to lead his civilian band throughout 1919 when not needed by the Navy. His 1919 civilian band tour across America and Canada left Sousa little time for family and the growing tensions on the home front.

His July 6, 1919, letter to Jane began, “Dearest wife. The same forces that silently and relentlessly led the world into a war…started an individual and family antipathy that has no parallel in history…Our family is not the only one…Philip’s contempt for Priscilla and Helen, Helen’s contempt for the rest, Priscilla’s indifference to me and you…make each other as unhappy as possible…The average person’s judgement about other’s affairs is usually of no value…Devotedly. Philip”

It is unclear what caused this animosity, but Sousa’s continuous touring with his civilian band most likely inflamed these tensions. However, by 1925 the tone of Sousa’s letters home had softened.

After his 71st birthday he wrote on November 11th, “My dearest little lady. In my courting days and after I used to write you at all hours of the night and day, but it has been some time since I wrote you at 5:15am…Many thanks for your birthday greeting…the Rotary Club and others entertained me in Peoria. I got more flowers than a blushing prima donna…I am in good condition, but a little shy on sleep…With much love, Philip.”

By 1929 his band’s touring schedule was limited to three months. When not on tour Sousa spent his time at home in Port Washington, New York. He wrote to Jane who was visiting her son and grandchildren in California, “Dearly Beloved, your telegram… came announcing your safe arrival…Priscilla and I were glad you…arrived safely. I do hope you’ll have a pleasant visit…Priscilla felt that I should be watched carefully and…not take more than an ounce of whiskey, all of which I obey as any dutiful and loving father should. But please tell her not to be so hard on a poor old father.”

The following March 21, 1930, Sousa wrote from Chicago’s Auditorium Hotel about his short trip to the University of Illinois to conduct his new “University of Illinois March” with Harding’s concert band. “My darling wife, I have had a rather hectic time since I left N.Y…Yesterday I drove out to the University 175 miles. They had a concert by the student band. They played splendidly. The students gave me a medal, the bandmaster gave me a baton, a medal, and their blessing…Ever your loving Philip.”

These brief samples from the Carter and Moore collection provide realistic insight of Sousa’s relationship with his family and help dispel the storybook portrayals of him as America’s March King. This newly acquired collection will be arranged and described this fall, and it will become available to anyone seeking a deeper understanding of Sousa’s life and career. For further information about the collection contact sousa@illinois.edu or call 217-333-4577.