In 1907, students from the Department of Electrical Engineering participated in a campaign to raise funds to build a memorial to Robert Fulton in New York City.[1] In order to contribute to this effort, Electrical Engineering students organized exhibition that displayed their work. Attracting 1,600 visitors and raising $250 to contribute to the Fulton memorial, the event would serve as the first Electrical Show. [2] As it expanded each year, the show was soon considered the “acme of development in electrical apparatus and experiments,” with its exhibits ranging from displays of practical items to spectacular and literally shocking devices.[3] While some of the exhibits illustrated futuristic items that could one day transform daily life, others sought to simply demonstrate how such inventions as the telegraph worked or to display new and improved household items. Programs from the 1910 and 1915 Electrical Shows mention exhibits on wireless telegraphy, vacuum cleaners, electric pianos, an “Electric Cafe,” and “the Wonder Tube”–the longest light on the university’s campus. A promotional video for the 1938 Electrical Show also promised to feature “man-made lightning,” “electrons at work” and a “kiss-o-meter”:

[ensemblevideo contentid=iLXPsQTbeES4kzmOR7Vniw]

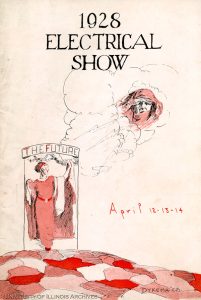

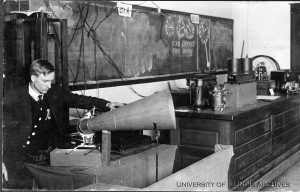

(Record Series 11/6/805)

The growth of the Department of Electrical Engineering mirrored developments and advancements in electricity, and thus the University of Illinois was considered the ideal place for the Electrical Show.[4] In addition to student exhibits and demonstrations, representatives from electric companies such as Westinghouse Electric, Edison Lamp Works, and the Manhattan Electric Supply Company set up booths to highlight their innovative products. Companies also lent patented technologies for exhibition, as the General Electric Company did in 1940 when it granted the University of Illinois a non-exclusive license to create a electro-magnetic levitator for the Electrical Show. [5]

While much has been written about the Electrical Show, and the tradition of the Engineering Open House that emerged from and existed concurrently with it (see the UIHistories Project and Engineering Open House blog post), the University Archives continues to acquire and preserve archival materials that highlight new aspects of the event that afforded attendees “a rare opportunity to learn everything about the practical as well as the theoretical uses to which electricity is applied.”[6]

[1] Ira O. Baker and Everett E. King, A History of the College of Engineering of the University of Illinois, 1868-1945 (Urbana: University of Illinois Libraries, 1947), 898.

[3] Curtis G. Talbot correspondence, 2/5/1936, Arthur C. Willard Papers, box 61, Record Series, 2/9/1, University of Illinois Archives.

[5] Charles E. Tullar to Ellery B. Paine, 3/1/1940, Arthur C. Willard Papers, box 61, Record Series, 2/9/1, University of Illinois Archives.

[6] “The E.E. Show,” The Electrograph, March 23, 1908, Record Series 11/6/805, University of Illinois Archives.