CW: Graphic Imagery

“Take it easy driving — the life you might save might be mine.” – James Dean, 1955

As citizens of the United States, we entrust our common defense and safety to the great leviathan called the federal government: sometimes that power manifests in the regulation and discouragement of behavior that puts lives – ours and others – in harm’s way. As a conduit for government initiatives, the Ad Council has encouraged safe driving habits for over 75 years. As administrations, automotive design trends, and public perception have shifted, the Council has remained steadfast on the importance of personal responsibility. Join us as we take a spin behind the wheel, exploring a multi-legged grand tour of Traffic PSAs from D-Day to today.

The enemy at home and the War abroad

In 1943, the engines of war hummed, well-oiled machines churned out weapons, munitions, and other goods essential to the war effort. Unfortunately, the cogs in the machines frequently caught themselves in the gears, limiting their usefulness, if not utterly destroying themselves. These critical components were the citizens left behind. According to President Roosevelt, more Americans were killed and injured in accidents than combat. Each life lost and day of work missed impacted the US’s ability to be the “arsenal of democracy” in the battle against the Axis Powers. To win the war, the Government needed to mitigate its losses at home.

Together with the Office of War Information (OWI), the Ad Council began its first campaign on public safety. The “Stop Accidents” campaign identified the four most common causes of serious injuries in the United States: traffic collisions, incidents at home, workplace accidents, and farming accidents. While wary of all injury causes, traffic accidents were of greater concern. Fewer men on the roads meant less traffic. Less traffic and increased levels of stress encouraged more reckless behavior from drivers. Like in our time, traffic deaths and injuries increased while the number of people on the road decreased. The OWI and the Ad Council recruited companies with appeals to patriotism, religion, and charity. Families, employers, and even Uncle Sam suffered when someone lost their ability to work. The publication of ads that emphasized caution could save countless lives. It was the right thing to do. It was the virtuous thing to do. Above all else, it was the Christian thing to do.

Switching Gears in Post-War America

The end of World War Two also marked a transition in focus for the Ad Council’s Stop Accidents campaign. During the war, the reduction of workplace injuries, especially in the expanded defense sector, was a matter of national security. For one reason or another, the Council dropped this point of emphasis in 1946.

Another change was the switch to seasonal press kits. The Green Cross/Stop Accident campaign released advertising kits themed around traffic and driving quarterly beginning in Fall 1948. Each season focused on the hazards (both natural and man-made) that were prevalent at those times of the year. Fall focused on drunk driving, changing weather patterns, and the dangers of nighttime driving. The winter kit emphasized the hazards caused by winter weather and not taking proper precautions when driving. Summer slammed speed demons and road-ragers.

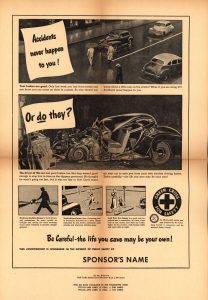

Within these kits were photographs and sketches of accidents. In an era before photographic ethics, some of these crash photos displayed the bodies of the deceased, showcasing the human toll of these preventable incidents. These images showed how quickly tank-like automobiles could turn into truncated tin cans. Like the CDC’s anti-smoking ads from the 2010s, the Ad Council hoped that showing disturbing images would discourage self-destructive behavior.

Another reason for the graphic imagery in the sample advertisements is convenience. The Council encouraged their advertising partners to create ads to supplement existing campaign materials. Major newspapers had entire collections of traffic accident photos to choose from to use in the campaign. Wesley Nunn, then coordinator of the campaign, wrote to newspaper ad reps in 1949, “a little digging in your own newspaper file should furnish some surprising facts about the frequency of local auto accidents. Use these clippings as sales ammunition to convince business, civic, and social groups of the need for support of this campaign.”

Under Nunn, the Stop Accidents campaign transitioned away from shock value in advertising. The first advertising kit issued under Nunn’s leadership included a mix of existing advertising and stencils. These stencils traced over pictures of auto collisions but removed any depictions of human remains. Compare these two kits, one from 1948 and another from 1949. The 1948 poster includes multiple photos from the same horrific car crash. A lone policeman lurks in the background, almost like the specter of death, with the deceased still behind the wheel of his automobile. The image is haunting, direct, and pulls no punches. The 1949 sheet, by contrast, is tame and tasteful. A destroyed vehicle takes center stage once again. Conspicuously absent is the presence of people. The before image clearly shows people crossing the street but removes them from the after shot. This ad asks the viewer to infer what condition the occupants of the wrecked vehicle are in instead of putting them on display.

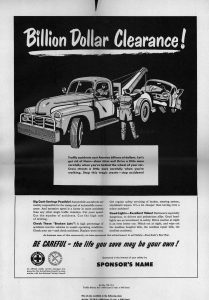

Initially appointed as the program coordinator for just 1949, Nunn assumed a permanent position as the lead for the Green Cross campaign. Nunn’s status allowed further control of the images chosen for Ad Council materials. Possibly inspired by the successful Tom and Jerry shorts of the time, the images became increasingly surreal and fantastical. Ad kits were light-hearted and built around a theme related to the time of year in which they ran. One example is the Fall 1952 kit, designed to resemble a liquidation sale of goods and accessories. Instead of fur coats and designer goods, accidents and bad driving practices were priced to move. Nunn believed that earlier campaign tactics did not get the public to buy into safety and caution. In a letter from 1952, Nunn said, “We want readers to think and feel our story [the Stop Accidents campaign] and act upon it. We are definitely selling this whole idea of accident prevention.”

Nunn’s run as the volunteer coordinator for the campaign ended in 1954. The final packet issued under Nunn’s stewardship was the Spring 1954 campaign, which introduced Alec, “the hero or villain” of the Stop Accidents campaign. Alec was the first character to fulfill a niche later occupied by Vince and Larry, the Crash Dummies. Within the developing Alec cinematic universe, he used his nine lives to demonstrate how self-destructive some actions were. While Alec could bounce back and land on his feet after calamities, humans could be gravely injured or worse if they followed his lead.

With the end of Nunn’s tenure came a complete refresh of the Stop Accidents campaign. Also departing was the Young and Rubicam Advertising Agency, which had produced campaign materials since 1947. Therefore it is only fitting that we end our tale here. What started as a wartime initiative blossomed into an eight-decade-long crusade against poor driving habits. While this concludes one chapter in the history of the Ad Council, countless stories are waiting to be told about the Council’s 80 years of public service advertising. Advertising provides a glimpse into the mindsets and culture of those who create it. If you are interested in discovering other hidden stories, I invite you to contact us at the University Archives by email or stop by for a visit.

Artifacts used

- 13/02/201 Box 3, Meeting Notes March 18th, 1949

- 13/02/201 Box 6, Meeting Notes February 26th, 1954

- 13/02/207 Box 2, Fight Waste/Stop Accidents: Your Advertising Can Save Lives, undated. #176

- 13/02/207 Box 5, Stop Accidents: Green Cross/Traffic Safety, Fall 1948. #437b

- 13/02/207 Box 6, Stop Accidents: Traffic Safety, Fall 1949. #457

- 13/02/207 Box 10, Stop Accidents: Summer Safety Kit, 1952. #622

- 13/02/207 Box 12, Stop Accidents: Spring Safety Kit, 1954. #689