How did you end up at the University of Illinois Archives? Tell us about your background.

In the summer of 2012, I held an internship at the National Music Museum in Vermillion, SD. This experience was a watershed moment for me, inspiring me to seek out as many archival experiences as I could. The following fall I enrolled in the musicology program at UIUC and in the summer of 2013, I took a course on Arrangement and Description. In the fall of 2013, I became a graduate assistant at the Sousa Archives and Center for American Music. Except for the 2018-2019 academic year, when I took a gap year to teach in the musicology department at Ball State University, I held this GA position until 2021. This was the year I earned my PhD in musicology. I explored many facets of archival work as a GA. I worked collaboratively with the other graduate assistants at Sousa, digitizing and writing metadata for the James Edward Myers WWI Sheet Music Collection, which can be seen in the digital library; processing faculty papers one summer; co-curating several exhibits on topics like campus protest music in 1970, SS Stewart banjos, Temperance-era sheet music, Bohumir Kryl’s Women’s Symphony Orchestra, and Hawaiian slide guitars; and assisting with programming for the One Community Together Soundstage and musical instrument “Petting Zoo” at the Urbana Sweetcorn Festival. My PhD research on concert life in Prairie Style architectural spaces was also influenced by the training I received as a GA, making use of materials found in more than thirty archives around the country.

After graduating with my PhD, I was offered a position as a lecturer in the musicology area here at UIUC. Fortunately, I was able to continue working at the Sousa Archives in a service-in-excess capacity until I earned this position earlier this year. Between 2021 and 2025, I have predominantly focused on exhibit curation and programming, working with Scott Schwartz to curate exhibits like the Imperfect Saxophone and Spaces Speak. During this time, I also worked as a consultant for the Old Town School of Folk Music, providing them with an assessment of their archives.

While this is a new position for me, the University of Illinois Archives has felt like my home for more than ten years.

What are your responsibilities?

Currently, I am responsible for processing our digital collections. The Sousa Archives hasn’t had a dedicated individual for digitized and digitally born materials for many years, so we have a bit of a backlog. I hope that I can process several of these collections over the summer and fall, providing online access to these collections within the Digital Library. In addition, we are performing a shelf-read this summer, confirming the locations of all our material at the Archives Research Center and barcoding all the collections there. After we finish this task, we will have exhibits and programming for American Music Month, the Uniting Pride Festival, and the Folk and Roots Festival to prepare. I’ll be working with Scott on programming for these events, plus a few more for the upcoming Semiquincentennial of the United States of America. As a “Center for American Music,” we’ll be preparing for this event soon. At some point I’ll need to tackle the stats for the summer, and we have three new collections that are in the queue, waiting to be processed.

I’m hitting the ground running!

What excites you most about your new role? What are some plans/ideas you have in mind?

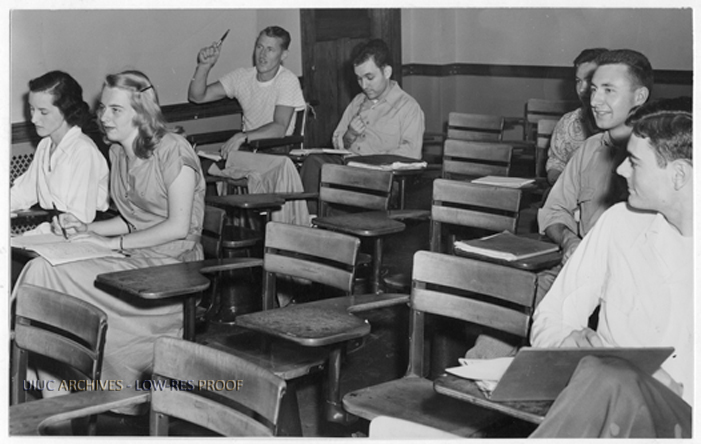

I am most excited about potential programming and pedagogical opportunities. My goal is to develop pedagogical opportunities with local public schools and build upon my experience as a university educator to help guide course design at the University. One of the plans I have is establishing collaborative opportunities with courses on history within the College of FAA. The idea of an “imbedded archivist,” like an imbedded librarian, is really intriguing to me. Embedding archivists within specific courses would provide students with better access to our collections and would help demystify the act of archival research. Although my background is in musicology, I do not think this type of collaborative course design should only consider music history courses. Since I have active interests and contacts in art history, architectural history, landscape history, and media studies, I won’t preclude other history courses in the humanities when reaching out to potential instructors. My plan is to begin gauging potential interest among a few programs in FAA at the beginning of August, when instructors are planning their syllabi.

In terms of public-school programming, I hope to establish working relationships with local school music programs and history departments. For instance, I think we could make a compelling case for adding a class on Music Research and Museums during the 2026 Illinois Summer Youth Music schedule. This is a program that predominantly serves junior and high school students. I think Sousa does a great job already reaching some of these junior and high school groups, but we could do more, especially with non-music students. It has also been a long time since we have regularly worked with the local elementary schools. As a father of a soon-to-be third grader and soon-to-be kindergartener, building relationships with the elementary schools in the surrounding area is especially important to me.

Although I am not teaching courses at the moment, I am hopeful that I can teach an occasional class that makes use of the collections at the Sousa Archives. Last semester I taught a class on exhibit curation and last summer I taught a summer MME class on the music of Illinois. Both of these classes spent several weeks at the archives, exploring the collections and developing unique projects based on the students’ findings. My Curating Communities class last semester designed a traveling exhibit on the Robert E. Brown Center for World Music that we took to Northern Illinois University’s Teaching World Music Symposium. The exhibit is currently on display in the Harding Band Building. My goal is to continue developing courses that make use of the materials at the Sousa Archives.

What are the most interesting/challenging/fun aspects of the job so far?

The thing I find most interesting or fun about working in the archives is that I get to learn new things every day. Last week, I was working on an alumni’s papers and found material relating to the UIUC Stunt Show in the 1960s. This event was new to me. On one of the Stunt Show programs, I learned that incidental music was provided by LeJaren Hiller (a chemist and composer that composed the first piece of computer-derived music). This event also included Bernard Goodman (Violinist with the Walden String Quartet), Stanley Fletcher (Professor emeritus in the Piano Faculty), and Jack McKenzie (Dean Emeritus of the College of FAA and Former Director of the UIUC Percussion Ensemble). After communicating with the donor, I learned quite a bit about this event and his involvement in the productions. I find that learning this type of information while processing collections can really help when working with patrons. The more you know the more you can help others.