This post is part three of the exhibit “Epidemic! Disease on Campus, 1918-1938.”

From 1840 until 1883, scarlet fever became one of the most common infectious childhood diseases to cause death in the major metropolitan centers of Europe and the United States, with fatality rates that reached or exceeded 30% in some areas. Until the early 20th century, scarlet fever was a common condition among children. Though the disease did not reach the epidemic heights of the late 1800s at the University during Doctor Beard’s tenure, the Health Services Station dealt with yearly threats of a potential disaster.

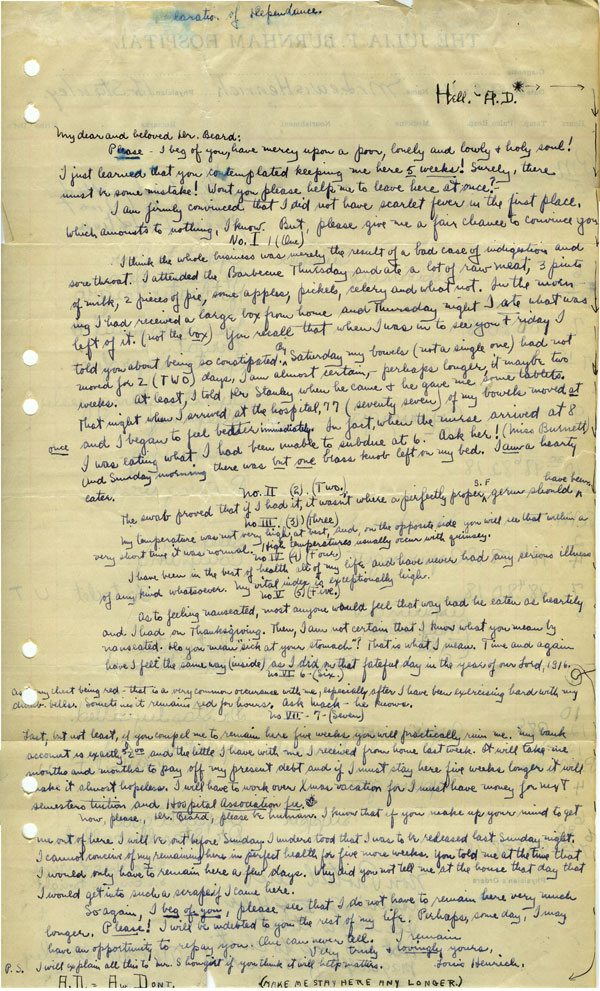

Found in Record Series 39/2/20

During each scarlet fever outbreak, J. Howard Beard made various public announcements to the student body about the importance of keeping quarantine. His public relations statement on April 3, 1935 eloquently targeted amorous students who risked quarantine to visit their love interest: “Although the world loves a lover, the scarlet fever germ is neither chivalrous nor romantic. It will send the betrothed to the hospital as quickly as the swain who has not yet met his fate…Telephone or send flowers, but take no chances of spreading a disease which may have serious consequences.”[1]

Students living in the same house as an ill person were tested for their susceptibility to scarlet fever using the Dick Test. Susceptible individuals developed skin reactions within 24 hours after the injection, and remained under house quarantine until threat of scarlet fever dissipated. In February of 1935, enterprising freshman William Kusz took advantage of a quarantine at the Phi Sigma Kappa fraternity house by massaging the injection site to simulate a positive result to the Dick Test. As expected, a physician placed Kusz under house quarantine and he cheerfully enjoyed the planned vacation. However, his seven day vacation evolved to two weeks because of further outbreaks, Kusz’s “former success began to wane and he became anxious concerning his scholastic future.”[2] Several weeks later, facing yet another quarantine because of his deceit, Kusz confessed his antics to the Health Services Station. His quarantine sentence was immediately rescinded after testing negative to a second Dick Test.

Quarantine doomed students and entire houses to a week or more of isolation, threatening their scholastic and financial status. Louis Joseph Henrich, an Education graduate student, was diagnosed with mild scarlet fever in December of 1916 at Burnham hospital. Upon diagnosis, he was placed under immediate hospital quarantine for five weeks and his housemates at 603 East Springfield remained under temporary medical observation and house quarantine.

Shortly after his internment, Henrich penned a humorous, desperate declaration of independence to Doctor Beard arguing his release from the hospital. Attributing his ill health to a barbeque feast of “raw meat, 3 pints of milk, 2 pieces of pie, some apples, pickels[sic], celery and what not”[3] and the subsequent inability to void his bowels, Henrich argued his release in seven steps. If the penmanship of the original document located at left is difficult to decipher, the transcription provides easier reading. Henrich’s detailed plea did not secure his freedom. He remained in quarantine through the winter holidays.

[1] “Beard Warns Against Quarantine Violation,” Daily Illini, April 3, 1935

[2] Campus Health Service Director’s Office General Correspondence, Record Series 33/1/1, box 1, folder “General Correspondence, T,” University of Illinois Archives.

[3] Campus Health Service Director’s Office General Correspondence, Record Series 33/1/1, box 1, folder “General Correspondence, H,” University of Illinois Archives.