The second of four posts written for “WWI and Champaign County” of the Town & Gown Speaker Series, a collaboration between the Student Life & Culture Archives and the Champaign County Historical Archives.

Research for this post contributed by Maggie Cornelius.

The United States government asked Americans to knit socks, sweaters, and other garments for soldiers during World War I. Most of this knitting was produced by volunteers working under the auspices of the American Red Cross. Illini women, like many women during the war, devoted their free time and money to contribute necessities and luxuries to the war effort. The former provided subsistence and the latter provided morale.

Committees appointed by the Council of Administration oversaw University war-relief efforts.[1] The Red Cross monitored many of the University volunteer efforts, and in October 1917, the Women’s League created a Red Cross workroom in the Women’s Building where students could stop by for a few minutes and “roll a bandage or knit or do some other Red Cross work.”[2] These bandages and garments were sent to aid soldiers at the front, who frequently requested socks and sweaters in their letters home. In order to keep up with demand, the Red Cross urged University women to spend one hour per week volunteering. Sororities frequently devoting one night per week in these work rooms.

In January of 1918, Washington sent a plea for surgical dressings to Red Cross chapters across the country, as France needed 30,000 surgical dressings a month to treat the wounded.[3] In response to the plea, Swariberg requested that University women register for a class on surgical dressings for the 1918 spring semester.

In February 1918, the University established its own Red Cross chapter and Swariberg became its head.[4] By May 1918, the University Red Cross met its yearly goal of 15,000 surgical dressings through the help of 300 workers, twelve of whom were awarded crosses for working 32 hours that semester.[5] Each week, the Daily Illini published the hours volunteered by organizations, motivating sororities like Kappa Alpha Theta, Delta Gamma, and Gamma Phi Beta to clock the most volunteer hours per week.

Wartime contributions of women at home did not go unnoticed by the men on the front. In a letter to his family, Francis Erle Cavette wrote:

In this hospital of Evacuation such as we have at Souilly, a large hospital with about 8 operating rooms, and beds for 3,000 to 5,000 in cases of Emergency. Here thousands of men are operated on monthly, and here thousands of American made bandages, shirts, etc. are used. The American made wrappings etc. are very useful being larger and better than those made in France.[6]

The Red Cross also sponsored the compilation of comfort kits for soldiers to take with them to the front. These kits included supplies for sewing, grooming, letter-writing, and miscellaneous items such as Bibles and cups. Although the U.S. military provided soldiers with necessities, comfort kits supplied soldiers with quotidian items that became novelties on the war front. Comfort kits included:

- khaki or white sewing cotton

- white darning cotton

- small round mirrors

- handkerchiefs

- writing pads

- envelopes

- postcards

- buttons

- blunt pointed scissors

- lead pencils

- Bibles

- cups

- safety and common pins

Despite their popularity with the soldiers, the Secretary of War and the Secretary of the Navy criticized the kits, saying “it seems incongruous, to say the least, that at a time when the nation should avoid luxury, thoughtless women should make our very army and navy the worst offenders.”[7] The Secretaries emphasized that the U.S. military provided soldiers with plenty of clothing and that Red Cross volunteers were mistaken in thinking their donations met a dire need. Nevertheless, the Secretaries admitted that the contributions “add to the fighting men’s happiness and hence their efficiency.” Undeterred by the military’s criticism, the Red Cross continued to compile and distribute comfort kits. By February 1918, every American soldier entered the trenches with a comfort kit.[8] Distribution of these kits continued until the end of the war.

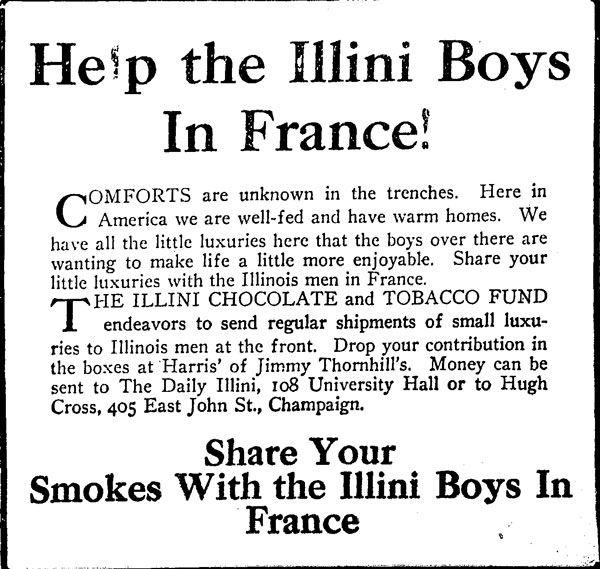

In the same spirit of luxury, the University also established the Illini Chocolate and Tobacco Fund in September 1917, which gathered donations to send to Illini fighting in France.[9] Over 130 boxes containing cigarettes, tobacco, and chocolate bars went to servicemen in time for Christmas 1917.[10] The Daily Illini reported that servicemen frequently requested chocolate and “smokes” because the former was scarce and the latter “rank” in France.[11] Upon receiving one of these packages, alumnus F. Lindahl Peterson wrote that “In a world of rain, discomfort, and work, and where good tobacco is unobtainable, nothing is more highly appreciated than American cigarettes.”[12]

The Chocolate and Tobacco Fund was just one fund-raising effort initiated by the University community. The Belgian relief fund, the Syrian-Armenian fund, the French ambulance fund, and the Women’s War Relief Fund also found support within the community. In a grand show of solidarity, Kappa Kappa Gamma chose to put the money they raised to buy a sorority house towards liberty bonds.[13] The YMCA’s drive was the most lucrative effort, raising over $28,000, ranking third among university YMCA funds across the country.[14]

[1] The Adelphean of Alpha Delta Pi, Feb. 1918, p. 91, Record Series 41/72/4, University of Illinois Student Life and Culture Archives.

[2] “Woman’s League to Start Proctor System in Units,” Daily Illini, September 26, 1917, p. 6.

[3] “Red Cross Makes Plea for Surgical Dressing,” Daily Illini, January 24, 1918, p. 2.

[4] “Student Women Now Have Separate Red Cross Unit,” Daily Illini, February 21, 1918, p. 5.

[5] “Red Cross Wants Weekly Services of 500 Students,” Daily Illini, October 24, 1918, p. 1.

[6] Francis Erle Cavette to family, September 21, 1917, War Service Records, 1917-1919, Record Series 41/2/17, Box 6, University of Illinois Student Life and Culture Archives.

[7] “Knitting Luxuries,” Daily Illini, December 5, 1917, p. 4.

[8] “Red Cross Kits Supplied All American Soldiers,” Daily Illini, February 26, 1918, p. 3.

[9] “Illini ‘Smokes’ Fund Launched,” Daily Illini, September 21, 197, p. 1.

[10] The Adelphean of Alpha Delta Pi, Feb. 1918, p. 91-92, Record Series 41/72/4, University of Illinois Student Life and Culture Archives.

[11] “Illini in France Appeal for ‘Smoke,'” Daily Illini, November 2, 1917, p. 1.

[12] “Illini in France Acknowledge Receipt of ‘Smokes’ and Candy,” Daily Illini, January 4, 1918, p. 5.