The third of four posts written for “WWI and Champaign County” of the Town & Gown Speaker Series, a collaboration between the Student Life & Culture Archives and the Champaign County Historical Archives.

Research for this post contributed by Maggie Cornelius.

America’s entry into World War I required the mobilization of the country’s brightest minds and ablest bodies for military training and leadership. The War Department looked to American universities to recruit capable men for its military departments. These recruitment efforts prompted the establishment of two prominent military organizations at the University of Illinois, both of which served as the foundation for the current Illini Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) program.

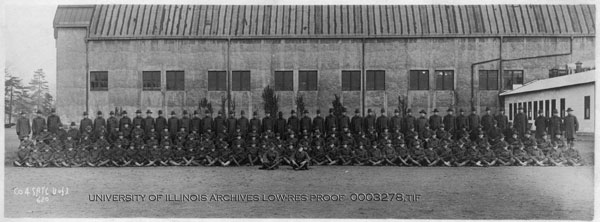

Prior to ROTC, the 1862 Morrill Act obligated land-grant universities to instruct its male students in “military tactics.”[1] Anticipating the American entrance into the war, the National Defense Act of 1916 established the ROTC as part of its reorganization of the American military. Illinois created its ROTC chapter in 1917 and fundamentally changed how the University fulfilled its Morrill Act obligation. ROTC’s primary purpose was to train and enroll men into the Reserved Officers’ Corps who were qualified to be “captains or lieutenants of volunteer organizations in times of war.”[2] In its early days, ROTC was divided into seven units: medical corps, signal corps, engineers, cavalry, field artillery, coast artillery, and infantry.[3]

ROTC enrollment was open to male university students over 14 years old who either passed a physical fitness exam or completed two years of brigade work.[4] Once enrolled, freshman and sophomore ROTC students spent three to five hours per week in military training classes in addition to their academic coursework. Cadets also had the opportunity to attend a two-week military training camp. Excellent upperclassmen who continued training spent five hours a week in military courses and attended a training camp four weeks out of the year. Students who completed four years of ROTC graduated as officers in the U.S. military and served up to four years.[5]

The Daily Illini deemed the ROTC “the most definite of the many opportunities offered for students to serve the country” because it equipped students to fight the war, rather than support it through second-hand efforts. University President James explained the utility of supporting the war through the federal government, rather than through independent university effort: “If a battalion of U of I students are to enlist, it will be far better for them to go as commissioned officers than as a single University unit. Two thousand student officers scattered throughout the Army can do a great deal more for the United States than two thousand enlisted men as a single unit.”[6]

Not long after the birth of ROTC, Student Army Training Corps (SATC) replaced campus military instruction. By May 1917, 1,000 men had withdrawn from the University to fight in WWI, leaving around 1,200 in the campus military department. The following fall, almost 3,500 Illini were part of the SATC which consisted of military, naval, and medical sections.[7] Students lived on the second floor of the Armory[8] and were identified by the “olive drab hat cord” worn with their military uniform.[9] To enroll, male students had to be high school graduates and physically fit. Members spent 13 hours per week learning military drill and tactics and three hours a week learning about war aims. In correspondence with serviceman Zean G. Gassmann, Dean Clark commented on the state of University:

Not long after the birth of ROTC, Student Army Training Corps (SATC) replaced campus military instruction. By May 1917, 1,000 men had withdrawn from the University to fight in WWI, leaving around 1,200 in the campus military department. The following fall, almost 3,500 Illini were part of the SATC which consisted of military, naval, and medical sections.[7] Students lived on the second floor of the Armory[8] and were identified by the “olive drab hat cord” worn with their military uniform.[9] To enroll, male students had to be high school graduates and physically fit. Members spent 13 hours per week learning military drill and tactics and three hours a week learning about war aims. In correspondence with serviceman Zean G. Gassmann, Dean Clark commented on the state of University:

“I laughed hysterically at your suggestion that with the present military situation here I would find my work at rest rather than otherwise. I have never been through such hell in ten years of my life as I have been through the last two months. The military people came in with the idea that this is a cantonment and not a college, and up to yesterday totally ignored the study schedule. We have an inspector here from Washington, and things began to change yesterday, though I suspect after the schedule of fifteen people at least has been ruined. We shall make the adjustment, but it will certainly take time. We have had less study and less discipline so far this year than any year of my acquaintance with college life, but I think it is going to change.”[10]

Despite the chaos induced by a military presence, the University community took care to preserve its identity as an academic institution. A Daily Illini editorial reminded SATC students that “Those of us who are members of the Student Army Training Corps have an additional responsibility to show that we are students…If [President James] and the War Department had desired to train the students as soldiers he would have sent them to a regular military cantonment.”[11] At the end of their ROTC training, students went wherever the government dictated. By the end of 1918, 150,000 men were involved in SATC around the country.[12] The SATC disbanded near the end of the war and ROTC reestablished just a few months later in January of 1919.[13]

Although mandatory military training for male students at land-grant universities ended in the 1960s, ROTC chapters continued at many land-grant universities, including the University of Illinois.

[1] University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Army ROTC, U.S. Army, http://www.goarmy.com/rotc/schools/university-of-illinois-at-urbana-champaign/history.html.

[2] “Welshimer Explains New Plan for Military at University,” Daily Illini, February 23, 1917, p.3.

[5] University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: What is Army ROTC?, U.S. Army, http://www.goarmy.com/rotc/schools/university-of-illinois-at-urbana-champaign/whatisrotc.html.

[6] “Students Await Call to Service,”Daily Illini, April 11, 1917, p. 5.

[7] Military Department History 1965-1921, Box 1, Record Series 27/1/5, University of Illinois Archives.

[09] Daily Illini, November 5, 1918, p.1.

[10] Dean Clark to Zean G. Gassman, War Service Records, 1917-19, Record Series 41/2/17, Box 1, University of Illinois Archives.

[11] “Steady,” Daily Illini, October 23, 1918, p. 4.

[12] T.J. Camp to G. Chapin, June 5, 1922, Committee on the History of the Participation of the University in World War I File, 1915-23, Record Series 4/5/50, University of Illinois Archives.

[13] “S.A.T.C. Boosts Colleges Attendance Says Report,” Daily Illini, December 14, 1918, p.2.